Beyond an Ounce of Prevention; The Immeasurable Worth of Social Support

By Stéphane Grenier, MHI Founder

In 1736, Benjamin Franklin advised Philadelphians threatened by fires that "An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure." Obviously, preventing fires is preferable to fighting them, but how well can we protect ourselves from them and what supports are in place for those who inevitably are impacted by a potential unpreventable hardship?

Over the past several decades, the concept of "prevention" has been examined from all angles. Without a doubt, if research findings had consistently indicated a tangible way for trauma-exposed workplaces to implement something that aids in mitigating the effects of horrific events on humans, action would have been taken.

Let me be bold and suggest that while we continue our efforts to prevent Post - Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other stress injuries, we should focus on the back end. Let's turn this around for a moment.

Imagine that a person about to receive a slap in the face was informed beforehand. As a means of preventing or mitigating the full impact of the slap and the potential for injury, the perpetrator proceeded to warn the person, describing the pain that would be experienced, the violent backward whipping of the head, the possibility of tears in the eyes, and the inflamed reddening of the skin on the cheek.

Despite all of this preparation and readiness, the effects of the slap will be minimally affected by all this preparation when the slap is received.

I recognize that this analogy is a stretch, but I share it to illustrate that those good intentions do not always produce the desired outcomes. As is the case for someone who has just received a slap in the face, I suggest that what will make a difference in a trauma-exposed workplace is not what we do beforehand but how we support individuals after the fact.

What am I getting at here?

Organizations, leaders, governments, and people in positions of authority must remember that when they employ people and put them in harm's way, whether it's a firefighter, sending a soldier overseas, a health care professional, correctional officer, border service employee, police officer, or paramedic, to name a few, there are operational stress injuries as a result. It comes with the nature of the work they do and expectedly. For example, when police officers are deployed in the middle of a riot, both physical and stress injuries will occur.

In light of the fact that leaders must account for this, they must implement the proper systems to help boost people's ability to face these challenges and better support them.

Providing first responders, such as police officers, for example, with a protective bulletproof vest and attempting to prepare them to be in the face of harm is certainly important, but we do not have a current solution for the prevention of a first responder developing a stress injury, PTSD, depression, and the like, after hardship.

Significant research needs to be done in this regard and the ongoing quest for effective resiliency training so that one day, people that we send to work and put in harm's way are never again affected by the psychological effects of harm. Until then, what we can do, however, is properly support our people after hardship has occurred. Support systems for the recovery of those who are injured are incomplete; simply clinical care or a debriefing or a referral to a psychologist is currently the common practice.

So why do we continue to search for solutions to prevent this from happening when the fact of the matter is first responders are getting physically AND mentally injured?

We need to support them long-term for years after the operational stress injury* and trauma has occurred, or hardship has been faced. This is the biggest gap in the system right now. This is where I think the balance needs to be achieved

* Operational Stress Injury is any persistent psychological difficulty resulting from operational duties such as law enforcement, combat or any other service-related duties. Individuals experiencing high levels of operational stress injury are at greater risk of suffering from depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder.

Everyone is for resiliency and for prevention, but there is no actual effective evidence-based way to prevent trauma. On the other hand, we know that the greatest predictor of who will struggle the most after trauma is a lack of social support. The antidote is the proactive implementation of robust peer support programs in the workplace to complement all of the current clinical efforts and foster a caring culture.

We do know that good social support (as depicted in the Brewin slide below) is the best predictor of positive health outcomes and psychological health outcomes after adversity and trauma; therefore, it is time to invest. Even though Brewin's research is 22 years old, it remains valid to this day.

Over the past two decades, I have interacted with hundreds of thousands of leaders who have asked me how they can make their people more resilient. How do I prepare them for the unimaginable so that they do not struggle afterward? Governments at all levels fund research to answer these questions. Researchers utilize grants, and philanthropists donate millions of dollars to research.

I have always supported Operational Stress Injury research and prevention of all types. However, the pursuit of this goal must not be disproportionate or unintentionally detrimental to the ability to intervene and assist those who are injured.

My request is that we bring balance to the situation.

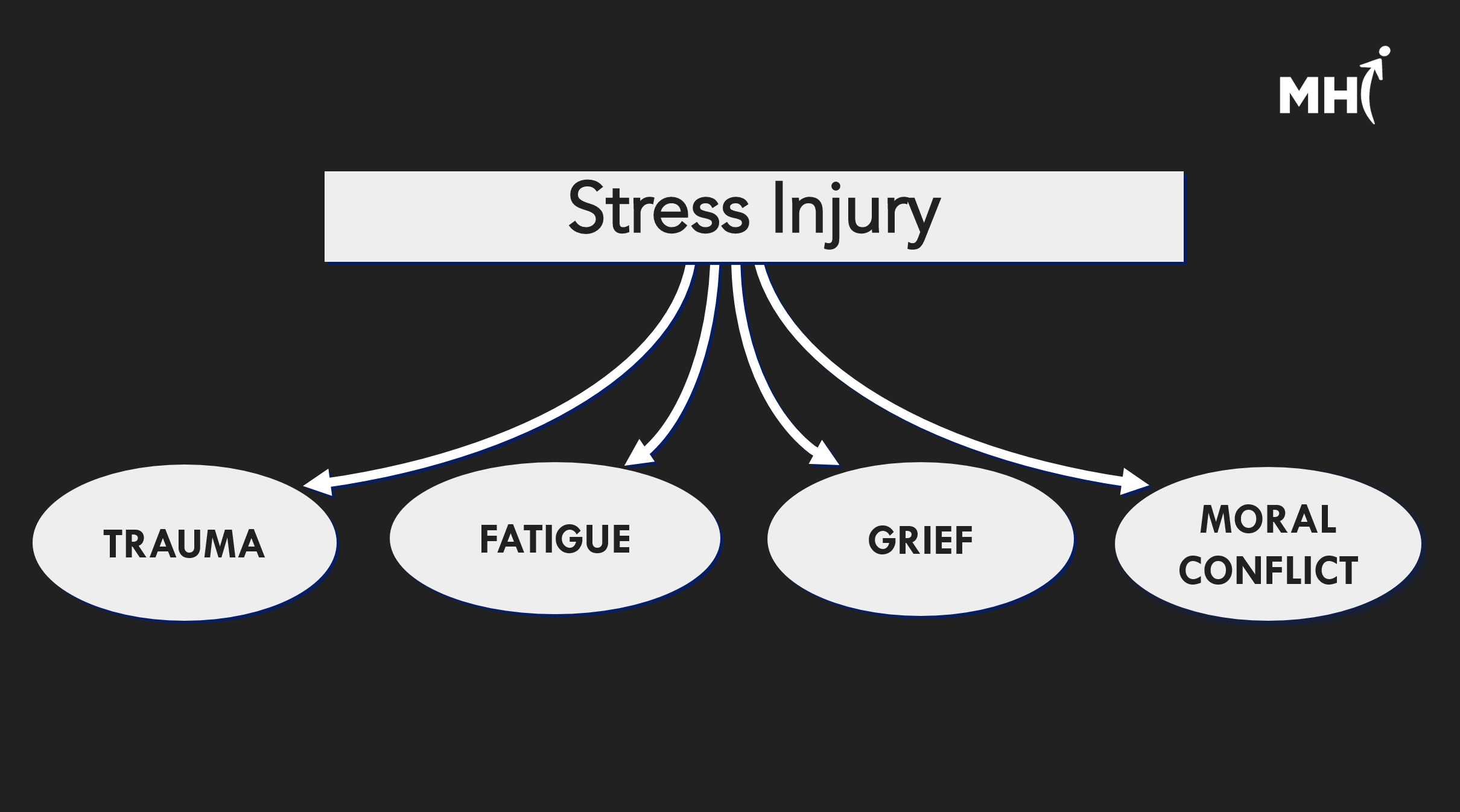

For each dollar spent on prevention, research, and conference attendance, we spend one dollar modernizing our social support system for those who continue to experience Operational Stress Injuries. That we not only focus on PTSD, but also implement support programs that go beyond a debriefing and referral, and the government and leaders stop focusing on PTSD and instead recognize that an equal number of people struggle with mental health conditions other than PTSD after adversity.

We’re here to help.

If you’re a first responder and would like to discuss how this might apply to your workplace, please connect with Stéphane.